Comment for CMS 4208 PJanuary 22, 2025 The Honorable Cheri Rice and Ing-Jye Cheng RE: CMS-4208-P: Medicare and Medicaid Programs; Contract Year 2026 Policy and Technical Changes to the Medicare Advantage Program, Medicare Prescription Drug Benefit Program, Medicare Cost Plan Program, and Programs of All-Inclusive Care for the Elderly Submitted electronically via regulations.gov Dear Honorable Cheri Rice and Ing-Jye Cheng, The American College of Physician Advisors (ACPA) is pleased to offer comments and information surrounding the Medicare Advantage program and data collection. American College of Physician Advisors represents more than 1173 members, spanning all 50 states. Physician advisors are healthcare professionals, often licensed physicians, who integrate utilization management, patient safety, care delays, medically appropriate treatment, clinical documentation improvement and care coordination and transitions, they frequently interface directly with health plans including Medicare Advantage organizations and plans. With this boots-on-the-ground insight into Medicare Advantage plan processes and how those processes interface with the actual delivery of healthcare treatment, physician advisors as an industry are uniquely positioned to offer insight to CMS on MA plans’ impact to patient care. Physician advisors are in a unique position to offer insight to CMS on many of the provisions proposed for Medicare Advantage plans. As more individuals select Medicare Advantage plans for their health coverage each year, the program must continue to evolve in a manner that is not only fiscally responsible for the Medicare trust fund and plans, but also financially viable for hospitals and healthcare professionals who fulfill Medicare Advantage organizations’ obligation to provide for Medicare benefits. Most importantly, the Medicare Advantage plan must work for patients. We appreciate the attention CMS is giving to a number of critical issues that affect patients’ care, their health, and the viability of their chosen healthcare professionals throughout the program nationally. Proposed Policies Must Protect Coverage and Payment for Basic Medicare Benefits.ACPA strongly supports CMS’s pursuit of MA plan policy that "[w]hen deciding whether an item or service is reasonable and necessary for an individual patient, we expect the MA plan to make this medical necessity decision in a manner that most favorably provides access to services for the beneficiary". We believe the patient’s healthcare coverage is of utmost importance in Medicare Advantage policy. Longstanding statutory requirements for MA plans to cover basic Medicare benefits in a manner that is no more restrictive than Traditional Medicare have been clear. CMS’s longstanding policy on these issues has been clear. CMS’s intent and requirements finalized in 4201-F were clear. To the extent there was any remaining doubt, CMS’s February 6, 2024 HPMS FAQ memorandum made unambiguously explicit what CMS’s expectations are for MA plans. Despite CMS’s extensive efforts to reiterate and emphasize these requirements, we continue to hear from members that MA plans continue to systemically engage in the concerning behaviors and practices CMS has described in 4208-P:

Further Clarification on Policy Will Not Effectuate Changed Behavior without Feedback and Enforcement MechanismsThese issues in MA plan practices are not founded in a lack of clarity in CMS’s policy. ACPA believes its members and their thousands of covered MA beneficiary patients will continue to struggle until there is structured and systematic evaluation, feedback, and enforcement of CMS’s clear policies. One hospital provided an example of an MA member who was denied access to inpatient rehabilitation services under circumstances that Traditional Medicare recognizes for coverage and payment. The member was not even offered skilled nursing facility care, but instead was authorized by the MA plan to receive home health services. At home, without the close physician monitoring needed to evaluate sensitive changes in the patient’s status, the patient quickly decompensated and by the time the severity of her condition was recognized by the next home health shift and she was taken to the emergency department, she unfortunately expired within only 48 hours of when she could have been admitted to covered inpatient rehabilitation. These and numerous other stories underscore that MA plan compliance with CMS directives is not merely an exercise, but quite literally and too often a matter of real patients’ life or their death. III. J. Ensuring Equitable Access to Medicare Advantage (MA) Services – Guardrails for Artificial IntelligenceHealthcare professionals, facilities, and patients are experiencing the detrimental effects from the use of artificial intelligence in utilization management. While plans have touted these processes as mechanisms to expediently approve care, patients and providers are not experiencing improvements in prior authorization turnaround time. Instead, members continue to report experiencing more denials, more obstacles, and more delays in getting their patients the care they need. ACPA supports the rationale behind CMS’s proposal to define automated system and to add new paragraph (ii) to 42 C.F.R. § 422.112(a)(8) requiring MA organizations to ensure services are provided equitably irrespective of delivery method or origin, whether from human or automated systems and specifying that artificial intelligence or automated systems, if utilized, must be used in a manner that preserves equitable access to MA services. ACPA further supports CMS’s emphasis that “[i]n the event that an MA organization licenses an AI or automated system, or contracts with a third party for services that are furnished using one of these tools, the MA organization will be held responsible”. 89 Fed. Reg. 99397 (Dec. 10, 2024). Definition of Automated Systems.We caution CMS in using the following phrase within the definition of automated systems: “As used in this part, automated systems that are within the scope of this definition are only those that have the potential to meaningfully impact individuals’ or communities’ rights, opportunities, or access.” For the reasons CMS cites pertaining to MA organizations’ longstanding misuse and misapplication of policy, this language has the potential to have unintended consequences by MA organizations. Just as CMS states MA plans mischaracterize organization determinations as payment policy or contractual denials, MA organizations can easily manipulate this draft language to suggest an automated system merely may effect individuals’ costs, but not “rights, opportunities, or access”. MA organizations may suggest so long as the member receives care they have not been deprived of a right, opportunity, or access to healthcare items or services. Because healthcare professionals and facilities are carrying out MA plans’ responsibilities to provide care to MA members under arrangement or under the promise of payment, ACPA encourages CMS to specify automated systems are those that also have the potential to impact coverage of and payment for healthcare services. ACPA further encourages CMS to emphasize that such systems fall within the definition so long as they have the potential to impact these issues. Definition of Patient Care Decision Support Tool. CMS’s proposal to define a patient care decision support tool consistent with the definition at 45 C.F.R. § 92.4 may create confusion, as that definition does not use the phrase “automated system”, and may be interpreted to be distinguishable from, and not to include, automated systems. CMS may further consider clarifying its explanation on the ways in which “MA organizations may use these systems” described on page 99398. For example, whether MA organizations are permitted to establish medical diagnoses if the MA organization is arranging for or paying for care as opposed to delivering care directly. Reference Definition of Artificial Intelligence. ACPA encourages CMS to explicitly reference and incorporate the definition of artificial intelligence at 15 U.S.C. § 9403(3) into the regulations for Medicare Advantage plans under rules for ensuring equitable access to services and under rules for the use of internal coverage criteria at 42 C.F.R. § 422.101(b)(6). CMS should continue to audit MA plans’ use of artificial intelligence, automated systems, and patient care decision support tools to ensure they comply with rules for equitable access and coverage criteria. CMS should also consider how the use of the tools would be able to comply with the public accessibility requirement at 42 C.F.R. § 422.101(b)(6). III. M. Ensuring Equitable Access – Enhancing Health Equity Analyses: Annual Health Equity Analysis of Utilization Management Policies and ProceduresACPA supports CMS’s proposal to require disaggregated metrics on prior authorizations, for patients with and without social risk factors, to illuminate metrics for health equity be reported for each item and service. We encourage CMS to specify these metrics apply to each of the three distinct periods during which coverage decisions are made – prior to service initiation, concurrent to service delivery, and after service completion. Decisions at each of these periods are organization determinations relevant to assessing MA plans’ health equity and utilization management practices. Specifically including concurrent and retrospective determinations, which are often made in relationship to urgent or emergently needed services, helps assess decisions which may disproportionately affect those with social risk factors, concomitant behavioral health issues, and generally more vulnerable patients. Including concurrent and retrospective determinations aligns with CMS policy in prior rulemaking in CMS-4201-F, when CMS emphatically reminded MA plans: CMS emphasizes here that section 1852(d)(1)(E) of the Act and § 422.113(b)(2) require coverage—which means payment—of emergency services defined under § 422.113(b)(1)(ii). Emergency services, under the statute and regulation, are covered inpatient and outpatient services that are furnished by a provider qualified to furnish the services and needed to evaluate or stabilize an emergency medical condition (determined using the prudent layperson standard). Further, emergency services must be covered regardless of the final diagnosis, consistent with § 422.113(b)(2)(iii), so the services needed to treat the emergency medical condition as presented therefore may not be retrospectively denied payment by the MA plan. (FR Vol.88, No.70, p22172) CMS should also ensure it defines “approval” and “denial” for purposes of this metric collection. For example, a denial of inpatient authorization is not an approval of an observation level of care; it is denial of access to, coverage of, and payment for the Traditional Medicare benefit that was requested: inpatient hospitalization. Similarly refusing to authorize a hospital stay within 30 days of a prior hospitalization is a denial of a Traditional Medicare benefit; not an approval of a “linked” or “interrupted” hospital stay. Retrospectively reducing coverage for an inpatient DRG or CPT by dictating specific definitions of medical diagnoses reduces coverage and payment for the incremental resources necessary to deliver higher levels of care and as such, is a denial with respect to coverage and payment for the DRG for which coverage and payment is requested by a hospital. For purposes of collecting and reporting on utilization management policies and procedures, CMS should consider any determination other than a full approval of coverage and payment of the originally requested services at the level, duration, units, or extent originally requested to constitute a denial. CMS should consider defining an original request, such as the provider’s first submission of a request for prior authorization or claim for reimbursement. CMS should consider incorporating guidance from its February 6, 2024 HPMS FAQ memorandum with respect to payment / reimbursement policy reviews versus organization determinations or level of care or medical necessity reviews: “We have heard frequently that MA organizations utilize post-claim review audits and examinations that routinely result in the denial of payment for the inpatient care that was provided to the enrollee. Further, we have heard that MA organizations characterize these reviews as “payment” reviews and that these reviews are “not organization determinations” or “level of care or medical necessity reviews.” We disagree with those characterizations of decisions that are denials of coverage or otherwise a refusal to provide or pay for services, in whole or in part, including the type or level of services, that the enrollee believes should be furnished or arranged for by the MA organization.” ACPA also encourages CMS to define what constitutes an approval “after appeal”. For example, as CMS discusses in 4201-F at p. 22223, “[peer to peer] discussions take place during adjudication of an organization determination”, but CMS also explains at p. 22198 “we interpret peer to peer review to mean a discussion between the patient’s doctor and a medical professional at the MA plan to obtain a prior authorization approval or appeal a previously denied prior authorization.” A peer to peer discussion is often the product of an MA plan’s communication of a denial or intent to deny authorization for a service. For that reason, ACPA recommends CMS include any overturn of a prior authorization determination as a result of a peer to peer discussion an approval after appeal. Doing so will help illuminate the additional administrative burden required to transform an adverse organization determination into a favorable one. ACPA further encourages CMS to expand the types of timeframes of prior authorization determinations MA plans would be required to report to CMS. CMS proposes to require MA plans to report average and median times for each covered item and service. The same principles CMS cited in hospital price transparency regulations at 84 Fed. Reg. 65526 (Nov. 27, 2019) apply to prior authorization metric reporting. CMS supported publication of certain price metrics so that “healthcare markets could work more efficiently and provide consumers with higher-value healthcare” by CMS “promote[ing] policies that encourage choice and competition”. Similarly, CMS believes enabling patients to become active consumers is critical so that they can lead the drive towards value. 84 Fed. Reg. 65526 (Nov. 27, 2019). CMS believed “the burdens placed on hospitals to make public their standard charge data is outweighed by the benefit that the availability of these data will have in informing patients regarding healthcare costs and choices and improving overall market competition.” 84 Fed. Reg. 65529 (Nov. 27, 2019). For all the same reasons, the minimum, average, median, and maximum timeframes for prior authorization reporting are important metrics to disclose for transparency, to make available to prospective enrollees via the Medicare Advantage Plan Finder site, to encourage compliance, promote competition, and encourage beneficiary choice of the plan that will best meet their needs. CMS may also consider clarifying that, while “the ability of the MA organization to decide which items and services are subject to prior authorization is not subject to rules on internal coverage criteria at §422.101(b)(6)”, utilization management tools are still subject to non-discrimination and health equity standards and cannot be utilized in a way that creates disparities in access to services. III. P. Format Medicare Advantage (MA) Organizations’ Provider Directories for Medicare Plan FinderHealthcare professionals, facilities, and Medicare Advantage organizations’ relationships are increasingly tumultuous, with MA plans exiting markets and their healthcare provider partners terminating contractual relationships. It is more important than ever for Medicare beneficiaries to have transparency in their health plans, including accurate provider directories within the Medicare Plan Finder at the point of health plan selection. ACPA encourages CMS to consider requiring MA plans to disclose or exclude any providers from its directory that have given the plan notice of an intent to terminate their contractual relationship with the MA plan. This will help ensure Medicare beneficiaries do not select plans, only to be surprised with a lack of access to their providers of choice in the event of a contract termination early in the plan year. Beneficiaries also deserve transparency in the same utilization management metrics CMS proposes to collect under its health equity initiatives, by benefit category such as hospitalization, inpatient rehabilitation, skilled nursing facility care, or advance diagnostic imaging. This information, which CMS is proposing to collect in III.M., should also be displayed in the Medicare Plan Finder. Making this information publicly accessible further promotes longstanding CMS policy that engaging and informing patients regarding healthcare choices, putting patients first and empowering them to make the best decisions for themselves and their families. Prospective enrollees should have access to information so they make informed decisions regarding their choice of health plan and empowering them to make the best decision for themselves. Prior authorization denial and approval metrics have the potential to directly impact the prospective enrollee’s access to needed care and financial responsibility. III. T. Proposed Regulatory Changes to Medicare Advantage (MA) and Part D Medical Loss Ratio (MLR) StandardsACPA supports CMS’s efforts to continue to refine how MA plans’ MLR is calculated, in furtherance of the initial intent “to create incentives for MA organizations and Part D sponsors to reduce administrative costs such as marketing costs, profits, and other uses of the funds earned by MA organizations and Part D sponsors and to help ensure that taxpayers and enrolled beneficiaries receive value from Medicare health plans.” 78 FR 31284 (July 22, 2013). Expenditures on quality improvement activities. ACPA shares CMS’s concern about variability in what some plans may consider to be a quality improvement activity and support CMS’s proposal that only expenditures directly related to activities that improve health care quality be included as “quality improving activity expenses” for purposes of MA MLR reporting. The current regulation at §422.2430(b) already excludes “all retrospective and concurrent utilization review” and the “portion of prospective utilization review that does not meet the definition of activities that improve health quality.” For clarity, CMS should consider specifying that reviews based upon MA plan payment / reimbursement policy or any substantively comparable programs whose purpose is to deny, reduce, or downcode coverage and payment of services – whether concurrently or retrospectively – are not quality improvement activity for MLR purposes. This would include, but not be limited to, concurrent and retrospective inpatient level of care reviews and reviews for clinical validation in which plans dictate and apply specific definitions of medical diagnoses to reduce the covered and payable DRG in inpatient care. Refusals to cover and pay for hospital readmissions is another risk area that CMS should thoroughly examine with respect to MA plan MLR reporting. 42 C.F.R. § 422.2430(a)(2)(ii) makes clear that only clinical interventions, such as education, counseling, and discharge planning should be considered quality improvement activities. Yet, many MA plans deny coverage of and payment for hospital stays within 30 days of a prior hospitalization under the guise of a quality of review. Aside from the tendency of these readmissions to be the result of the MA plan’s own denial of the appropriate level of post-acute care following the index hospital stay, these readmission reviews are not quality improvement activities but merely inappropriate cuts in coverage and reimbursement without actionable steps for prevention. As such, CMS should specify these concurrent or retrospective reviews are not only prohibited as more restrictive than Traditional Medicare, but are also not quality improvement activities. CMS should further investigate whether such activities are leading to under-reporting of actual readmissions in Part C Star Rating metric C15 All Cause Readmissions. Many MA plans’ mechanism for refusing coverage and payment for a second hospital stay involve a claims processing scheme to combine an index and subsequent stay into a single claim and single DRG payment, or alternatively instructing the hospital to rebill one of the stays as observation, with the potential to circumvent the HEDIS definition of All Cause Readmissions and artificially skew the plan’s readmission metrics. We further ask CMS clarify and re-emphasize the MLR excludes marketing as a quality improvement activity as established at 78 FR 31284 (July 22, 2013), and that agent and broken compensation is similarly excluded from quality improvement activities as established therein. Quality incentives. ACPA further supports CMS’s proposal to establish clinical or quality improvement standards for provider incentives and bonus arrangements in order for those incentives to qualify for MLR reporting. We agree with CMS’s proposal that a plan’s administrative costs to administer those incentives should be excluded, and agree with the rationale for this proposal that MLR should reflect expenses directly contributing to the value of coverage and care rendered to beneficiaries. In addition to the examples CMS cites of the types of incentive payments that may be currently captured by MA plans as quality incentives, some MA plans’ incentive programs include fixed components not tied to quality or outcomes such as cost of living adjustments or CPI adjustments. Other clarifications. Aligning with other policy set forth throughout CMS’s proposals, we encourage CMS to re-emphasize that claims incurred expenditures only include actual payments to providers. For example, if an MA plan’s contracted rate for a hospital stay is $10,000 but the MA plan denies coverage and payment for portions of the care, and as a result only remits $7,000, its incurred claims expenditure is $7,000 and not $10,000. We encourage CMS to emphasize that, like hospital cost reports, actual costs and not inflated rates should be used for MLR reporting. III. U. Enhancing Rules on Internal Coverage CriteriaInternal coverage criteria can only be used if additional, unspecified criteria are needed to interpret or supplement the plain language of applicable Medicare coverage and benefit criteria in order to determine medical necessity consistently. ACPA support CMS’s proposal to add the term “plain language” to §422.101(b)(6)(i)(A), and agree with the need to make it explicitly evident to MA plans that criteria may only be used to supplement or interpret existing content within Medicare coverage rules, and not to add new, unrelated criteria for an item or service that has existing but not fully established coverage policies. We agree with and support CMS’s intent that the MA organization identify the plain language of the applicable Medicare coverage and benefit criteria that they are interpreting or supplementing in the publicly available material and provide an explanation of the rationale that supports the adoption and application of the internal coverage criteria. CMS should also consider incorporating language from its explanation within 4208-P explicitly into regulatory text: “Internal coverage criteria may only be used to supplement or interpret already existing… Medicare coverage and benefit rules. In other words, internal coverage criteria cannot be used to add new, unrelated (that is, without supplementary or interpretive value) coverage criteria for an item or service that already has existing, but not fully established, coverage policies.” FR Vol.89, No.237, p.99456 CMS may consider using the two-midnight rule as an example of the plain language requirement, given the ongoing abuse of inpatient status denials by MA plans. MA plans continue to cite proprietary products such as MCG or Interqual to deny an inpatient level of care. CMS may consider explaining or even explicitly adding to regulatory text, as it stated in its February 6, 2024 HPMS FAQ memorandum and 4201-F, that the evaluation of the admitting physician’s expectation at the time of admission should defer to the judgment of the physician and such internal coverage criteria can only be used to assess the reasonableness of the physician’s judgment. As CMS has previously emphasized, clinical evidence and internal criteria must support the proposition for which they are used – in other words, there must be high quality clinical literature or widely used treatment guidelines describing the likelihood of requiring care that would span fewer than two midnights before such criteria could be used to usurp the admitting physician’s reasonable judgment on the expectancy of two midnights of hospital care based upon the plan language of 42 C.F.R. § 412.3. Definition of and Requirements for Internal Coverage Criteria. ACPA supports CMS’s proposed definition of internal coverage criteria at 422.101(b)(6)(iii): Internal coverage criteria are any policies, measures, tools, or guidelines, whether developed by an MA organization or a third party, that are not expressly stated in applicable Medicare statutes, regulations, NCDs, LCDs, or CMS manuals and are adopted or relied upon by an MA organization for purposes of making a medical necessity determination at § 422.101(c)(1). This includes any coverage policies that restrict access to or payment for medically necessary Part A or Part B items or services based on the duration or frequency, setting or level of care, or clinical effectiveness. CMS should also consider defining “level of care”. MA plans construe this phrase to compare levels such as inpatient, observation, inpatient rehabilitation, skilled nursing facility, home health, or hospice. However, MA plan criteria such as those which dictate specific definitions of medical diagnoses in a manner that reduces the covered diagnostic related group are also criteria which affect the level of care. Each DRG represents a combined group of resources to care for patients’ conditions. A reduction in the DRG based on anything other than ICD-10-CM Official Guidelines for Coding and Reporting is a reduction in the level and extent of covered and payable services. CMS should also consider clarifying that internal coverage criteria are any “policies, measures, tools, or guidelines – regardless of the label used to identify such criteria”. One prominent MA plan uses the term “protocol” to refer to parameters that dictate specific definitions for medical diagnoses and has openly asserted that its “protocol” falls outside the scope of internal coverage criteria merely because of its naming convention. We and our members are concerned, however, with CMS’s proposal to remove the requirement at §422.101(b)(6)(i)(A), that additional criteria provide clinical benefits that are highly likely to outweigh any clinical harms, including from delayed or decreased access to items or services. CMS should not remove a well-intended and justified regulation because CMS has found it difficult to definitively prove through evidence and enforce, nor because it observes “numerous instances of MA organizations simply and baldly stating that their internal coverage criteria provide clinical benefits that are highly likely to outweigh any clinical harms” without “much in the way of evidence in the information provided by the MA organizations that definitively proves this to be true”. We are concerned this logic only perpetuates MA organizations’ practices by hoping systemic misuse of guidelines will effectuate a change in policy rather than adamant enforcement. The expectation that internal coverage criteria have clinical benefits highly likely to outweigh clinical harms is entirely justified and is analogous to CMS standards for Medicare Administrative Contractors’ standards for developing local coverage determinations (LCDs) in 2018 to help improve transparency and consistency. As CMS highlights, a major difference between MA plans’ internal coverage criteria and NCDs, is the availability of public meetings and comment during the LCD or NCD process “to identify gaps or lack of clarity in a proposed policy” so that “as a result, the evidence-based coverage criteria are as specific as possible upon finalization.” 89 Fed. Reg. 99456 (Dec. 10, 2024). MA internal coverage criteria development are devoid of a public input process but still affects coverage and access to basic Medicare benefits in the same way as MAC LCDs. The absence of a public notice, comment opportunity, and consideration by MA plans during coverage criteria development warrants heightened standards for MA plans. As an alternative to eliminating the requirement to state with specificity clinical benefits highly likely to outweigh clinical harms, consider requiring the same elements of a valid LCD request:

Not only is it justified to impose a standard that internal coverage criteria are supported by clinical benefits that are highly likely to outweigh clinical harm, but the standard of “highly likely to outweigh” is not unique among healthcare regulations. Under HIPAA regulations prior to 2013, a determination of whether a breach of protected health information has occurred has been subject to a similar scrutiny of where there was a significant risk of harm to the individual. In modified rules, CMS characterized breach reporting standards to consider where there was a low probability the privacy of a patient’s information had been compromised. CMS intentionally avoided a bright line rule or standard under HIPAA regulations. When healthcare coverage determinations are at issue, a bright line and objective standard is impossible, but establishing a strong standard that any criteria which have the potential to obstruct access to healthcare services must be highly likely to outweigh identifiable clinical harms, CMS promotes its published policy that "[w]hen deciding whether an item or service is reasonable and necessary for an individual patient, we expect the MA plan to make this medical necessity decision in a manner that most favorably provides access to services for the beneficiary". 88 Fed Reg 22188 - 22189 (April 12, 2023). Any criteria that is not highly likely to offer benefits that outweigh clinical harms would fail to satisfy CMS’s expressed policy intent. Financial considerations are not clinical benefits. ACPA supports CMS’s proposed change in verbiage to make it explicitly evident that “a coverage criterion is prohibited when it does not have any clinical benefit, and therefore, exists to reduce utilization of the item or service” at 42 C.F.R. § 422.101(b)(6)(iv)(A). CMS may consider clarifying in this language “any coverage criteria or criterion is prohibited…” to avoid MA plan schemes to categorize coverage policy as criteria or criterion in an effort to circumvent CMS’s unambiguous intent. Specific definitions of medical diagnoses, clinical validation. ACPA further asks CMS to directly address the issue of MA organization criteria which dictate specific definitions of medical diagnoses. These criteria are often used in a process called clinical validation reviews, and we continue to hear from members clinical validation reviews have increased exponentially in the last five years with dramatic administrative burden and financial implications. While clinical validation is distinct and separate from DRG validation, MA plans often use the two terms interchangeably. However, DRG validation and clinical validation have distinct impacts. The former services to apply ICD-10-CM Official Guidelines for Coding and Reporting by ensuring diagnosis and procedure codes assigned on an inpatient claim are consistent with documentation in the medical record by qualified healthcare professionals legally responsible for the patient’s diagnosis and care. The latter, clinical validation, ignores documentation in the medical record of the very healthcare professionals who are legally responsible for the patient’s diagnosis and care and serves to “re-derive” a DRG as if documented diagnoses did not exist. The result is a reduction in coverage and payment for the incremental resources typically involved in the evaluation, diagnostic workup, and monitoring of the diagnosis at issue. In 4201-F, CMS wrote that: Finally, in response to whether prior authorization policies or procedures that dictate specific definitions of medical diagnoses is considered more restrictive than Traditional Medicare, we consider coverage policies that dictate specific definitions of medical diagnoses to be additional coverage criteria that are only authorized in accordance with §422.101(b)(6) as finalized in this rule. FR Vol.88, No.70, p.22202 CMS should codify a declaration that an MA plan’s internal coverage criteria – that is, any policy, measure, tool, guideline, protocol, or rule, regardless of the label used to describe such criteria, which dictates specific definitions of a medical diagnosis—are internal coverage criteria. As such, they must meet the requirements of §422.101(b)(6) including that they be publicly accessible and be based upon the high quality clinical literature required in such regulation. CMS should also clarify that to the extent any criteria dictating a specific definition of a medical diagnosis meets the regulatory requirements at 42 C.F.R. §422.101(b)(6) and is put into use by an MA plan, the MA plan cannot use any documentation related to a diagnosis for which the MA plan disallowed as “clinically invalid” in accordance with any such internal criteria, when reporting member diagnoses to CMS for the plan’s HCC data. In other words – if the MA plan deems a diagnosis invalid and does not pay a hospital for the incrementally higher resources to evaluate and treat the diagnosis, the MA plan should not be permitted to profit from the diagnosis and receive higher PMPM payments from CMS for the affected member for the affected diagnosis. For example, members continue to report MA plans reduce coverage and payment for hospital inpatient services by apply MA plan internal criteria dictating a specific definition for sepsis or acute respiratory failure. In doing so, the MA plan disregards the diagnosis deemed “clinically invalid” and remits payment in accordance with the DRG that would be assigned if the “clinically invalid” diagnosis did not exist at all on the hospital’s claim. In other words, the MA plan does not cover nor pay the hospital for the resources to evaluate and treat the sepsis, acute respiratory failure, or similar diagnosis. When the MA plan is reporting members’ diagnoses to CMS, sepsis and acute respiratory failure are designated HCCs. The MA plan should not be permitted to report these diagnoses to represent heightened acuity of the MA plans’ covered member if the MA plan deemed the diagnoses invalid and refused to cover and pay for their evaluation and care. Readmissions. CMS should consider stating that criteria used by many MA plans to deny coverage and payment for readmissions – whether through denial of prior authorization for the inpatient hospitalization, reduction in the approved level of care to observation, combining an index and subsequent stay into a single admission and single claim, or any other mechanism – can only apply the plain language of CMS rules for repeat admissions such as those at IOM 100-04 Chapter 3 Section 40.2.5: “QIOs may review acute care hospital admissions occurring within 30 days of discharge from an acute care hospital if both hospitals are in the QIO’s jurisdiction and if it appears that the two confinements could be related. Two separate payments would be made for these cases unless the readmission or preceding admission is denied” interpreted in conjunction with IOM 100-10 Chapter 4 Section 4240: “Obtain the appropriate medical records for the initial admission and readmission. Perform case review on both stays. Analyze the cases specifically to determine whether the patient was prematurely discharged from the first confinement, thus causing readmission. Perform an analysis of the stay at the first hospital to determine the cause(s) and extent of any problem(s) (e.g., incomplete or substandard treatment). Consider the information available to the attending physician who discharged the patient from the first confinement. Do not base a determination of a premature discharge on information that the physician or provider could not have known or events that could not have been anticipated at the time of discharge.

Deny readmissions under the following circumstances:

CMS should consider clarifying that for purposes of this policy, a medically unnecessary readmission means the admission fails to meet the definition of reasonable and necessary at § 1862(a)(1) of the Act – that is, the admission was not reasonable and necessary for the diagnosis or treatment of illness or injury or to improve the functioning of a malformed body member. CMS should also consider clarifying that any premature discharge that was based upon the MA organization’s own refusal to continue to authorize hospital care must be excluded. CMS should consider referencing IOM 100-10 Chapter 4 Section 4255.C to describe circumstances suggesting a circumvention of the PPS DRG system by the hospital: “Following are the four types of prohibited actions:

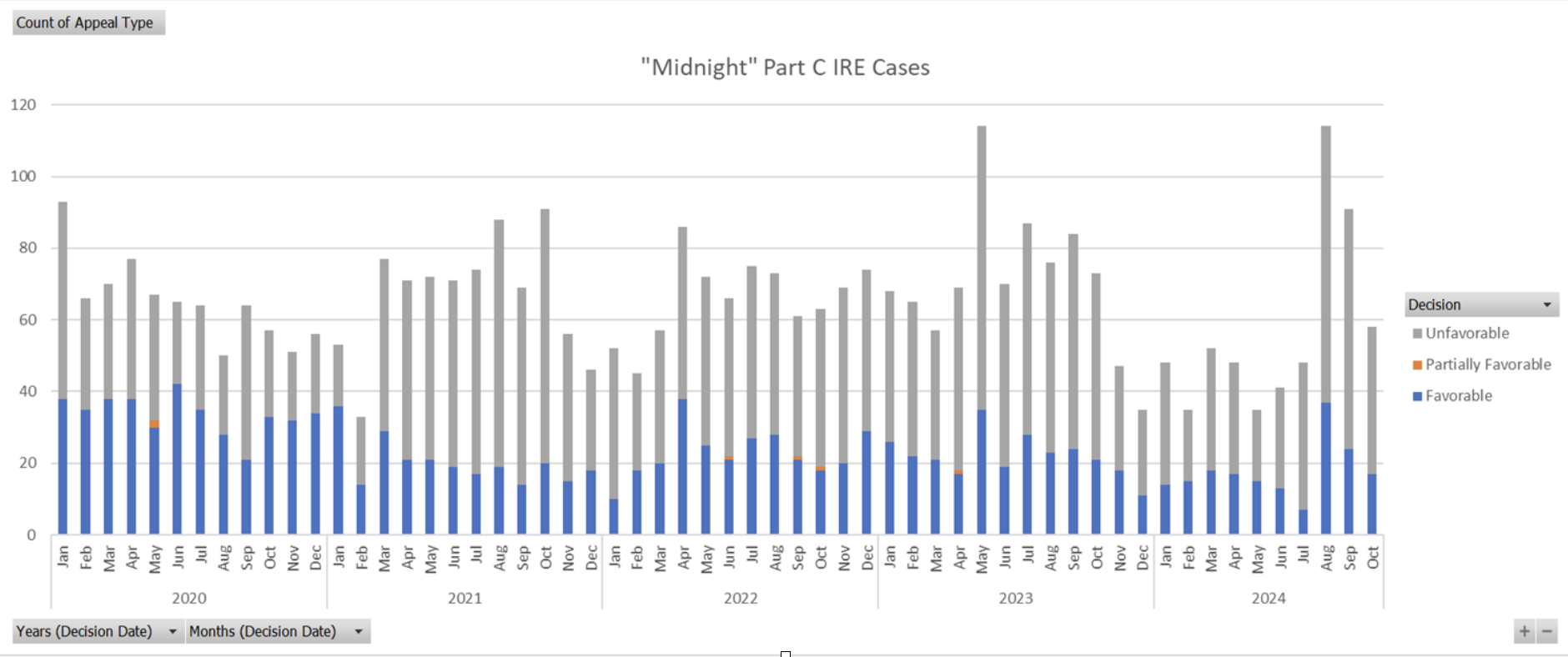

Because a determination as to the patient’s medical stability is a question of medical judgment, the MA plan should be required to use a physician with expertise in the condition(s) at issue to opine on the patient’s medical stability at the time of discharge. Plans should be prohibited from claiming a premature discharge as the basis to deny a readmission when the plan denied coverage and payment for continued hospital care during the index stay; when the MA plan did not authorize the level of post-acute care requested at or prior to the time of hospital discharge based upon the hospital or as applicable post-acute care facility’s original request. Public availability of coverage policy. ACPA supports CMS’s proposals to require each single coverage criterion to be listed and identified by the MA plan, to properly distinguish what is a plan coverage criterion versus Traditional Medicare policy. We further support the proposed requirement to connect each coverage criterion with a corresponding footnote linking to the specific evidence which supports the criterion, with an emphasis that any evidence and its underlying source must support the exact criterion being advanced and agree this helps align MA coverage criteria with formatting used in NCDs and LCDs. ACPA supports the requirement that MA plans’ public websites display of all items and services for which the MA organizations use internal coverage criteria when making medical necessity decisions. We urge CMS to clarify its statement that this requirement would apply to all internal coverage criteria, not just “when making medical necessity decisions” 89 Fed. Reg. 99461 (Dec. 10, 2024). The phrase “when making medical necessity decisions” may be manipulated and applied in a manner that suggests criteria do not need to be posted if they are not used at the time of a medical necessity determination. Rather, we believe it is CMS’s intent that coverage criteria would be required to be posted if used to make any organization determination, regardless of whether the determination is made prior to service, concurrent with service, or retrospectively. ACPA supports CMS’s proposal that MA organizations would be prohibited from limiting access to internal coverage criteria in a way that requires an account, a password, or disclosure of any personal information. We suggest CMS consider linking the MA plans’ internal coverage criteria websites on the Medicare Plan Finder so prospective enrollees can better understand how a plan makes coverage decisions. MA plans that currently require input of information to access these materials may deter beneficiaries from proceeding to review the information out of fear their health plan will discriminate against them based upon their health status. For example, a member seeking to review coverage criteria for advanced diagnostic imaging to examine a mass for potential malignancy may be deterred from reviewing such criteria if they are asked to input their name or other identifiers before being directed to the criteria. As a future enhancement, we suggest that CMS consider creating a Medicare Advantage Coverage Database analogous to the Medicare Coverage Database which would allow searching internal coverage criteria across plans and in specific jurisdictions that can enhance transparency for both providers and patients. Prohibitions on the use of internal coverage criteria. ACPA supports CMS’s proposal to universally prohibit MA plan coverage criteria when it does not have any clinical benefit, and therefore, exists to reduce utilization of the item or service. For example, an MA plan’s internal coverage criteria dictating a specific diagnosis for sepsis are not expressly stated in applicable Medicare statutes, regulations, NCDs, LCDs, or CMS manuals and are adopted or relied upon by an MA organization for purposes of making a medical necessity determination with respect to the level of inpatient care covered and paid through the resulting DRG. III. V. Clarifying MA Organization Determinations To Enhance Enrollee Protections in Inpatient SettingsClarifying When a Determination Results in No Further Financial Liability for the Enrollee ACPA strongly supports the proposal that the MA organization’s determination that an enrollee has no further liability must be made in response to a healthcare provider’s request for payment. We recommend additional explicit regulatory language at 42 C.F.R. § 422.562(c) that a request for payment must include submission of a claim for the services at issue from either the provider or the enrollee. Without such clarification, MA plans may try to define a notice of admission or similar concurrent provider communication to the plan as a request for payment under proposed § 422.562(c). This is further necessary as CMS instructs MA plans to process post-service but pre-claim authorization requests from providers as payment requests. (FR, Vol. 89, No. 237, p.99466) However, in this instance there would be no claim, and hence there should be no determination of enrollee liability. ACPA further suggests that CMS explicitly confirm that under existing interpretation of § 422.562(c), prior to 1/1/2026, enrollees have had the right to appeal denials of inpatient admission or other denied services prior to service completion. However, even this proposal would only partially close a major loophole that many MA plans have widely exploited to deny services that would have been covered under FFS Medicare, without CMS visibility. Members continue to report that MA plans routinely make organization determinations after claim submission. Denials such as DRG downgrades, clinical validation denials, cost outlier line-item denials, and readmission denials all meet the definition of an organization determination, but often (and for some of these by definition) these adverse coverage and payment determinations occur after claim submission. Clinical validation and readmission denials also generally involve use of MA internal coverage criteria to effectuate these reductions in coverage and payment. Under this proposal, a non-contracted provider could appeal these adverse organization determinations by becoming the assignee of the enrollee. However, the enrollee and contracted provider would still have no CMS administrative remedy under Subpart M, despite these denials not having anything to do with a “price structure for payment” as implicated by the non-interference provision. Providers are seeing significant increases in these types of adverse organization determinations, which are often now being issued with minimal clinical justification, or simply labeled as a payment policy. CMS has already identified and raised a concern with such characterizations in its February 6, 2024 HPMS FAQ memorandum. MA plans tend to be increasingly focused on these types of denials of coverage and payment because, strategically, they can only be externally contested through judicial action by a contracted provider. We ask CMS to further consider how MA incentives can focus on steps that actually improve enrollee health, rather than cost savings through administrative denials because fair adjudication is difficult and costly to obtain. ACPA asks CMS to reconsider in future guidance the current interpretation of the words “furnished by an MA organization” in 422.562(c). If care provided by a contracted provider is considered “plan-directed care” as CMS explains at 89 Fed. Reg. 99462 (Dec. 10, 2024), then it is a reasonable consequence that the plan has approved and must pay for that care. This is especially important when services involve emergency outpatient and inpatient services, where coverage and payment are required by SSA §1852(d) and §422.113(b) “without regard to prior authorization or the emergency care provider’s contractual relationship with the organization.” If Subpart M cannot provide administrative remedy for this statutory and regulatory requirement, then perhaps CMS may consider rulemaking within Subpart C where these protections are codified but lack any enforcement avenue. Clarifying the Definition of an Organization Determination to Enhance Enrollee Protections in Inpatient Settings ACPA supports the clarification that the timeframe of the denial decision, whether pre-service, concurrent to service, or post-service does not change the fact that a denial (such as an inpatient level of care denial) is an organization determination for which enrollees must be provided notice and afforded Subpart M appeal rights. We ask that CMS make clear that this is a clarification of long-standing policy and not a new policy. CMS astutely acknowledges that some MA plans inappropriately deny enrollee appeal rights for in-network inpatient services for a “myriad” of reasons. The biggest reason is that MA plans have been able to block enrollee appeals of in-network denials from entering the CMS administrative appeals process. In this process, the MA plan performs the 1st reconsideration, and the CMS IRE (Maximus) performs the 2nd reconsideration. Maximus is currently only permitted to accept denial reviews if sent by the MA plan itself, and not from any other party. In 2022, CMS finalized a process for Maximus’ review of MA plan dismissals of enrollee appeal requests. However, Maximus is currently only permitted to accept a dismissal review if the requesting party produces a Notice of Dismissal, which can only be issued by the MA plan. Thus, some MA plans have put in processes that violate multiple federal regulations by ignoring enrollee concurrent inpatient appeals (§§422.578, 584), failing to forward them to Maximus (§422.590), and failing to issue a Notice of Dismissal (§422.582). The cumulative effect of these violations is that the member is deprived of due process, the MA plan avoids payment for services, and CMS lacks visibility into these actions. Data from January 2020 through October 2024 pulled from the CMS IRE searchable database show that Maximus processes about 400 MA reconsiderations per day, but only 2 per day (0.5%) on average are appeals related to inpatient level of care. No apparent increase in Maximus inpatient level of care decisions was seen in 2024 despite the regulations from CMS-4201-F being in effect. This data is displayed below.

We appreciate and support additional regulatory clarity, but the main problem that must be addressed is that there is no avenue today for enrollees to appeal their inpatient denials via Subpart M that does not require some action from the MA plan – generally either a forwarding of an upheld appeal to Maximus or issuance of a Notice of Dismissal. Corrective actions could be to allow enrollees and their advocates to send cases directly to Maximus if the MA plan’s timeframe for an appeal decision passes without decision, and to require Maximus to review a failure to issue a Notice of Dismissal from any party to the decision. Strengthening Requirements Related to Notice to Providers ACPA agrees that the enrollee’s provider is often in the best position to receive, explain, and timely act upon the MA organization decision for an enrollee. We support the proposals to require the enrollee’s provider to also receive notification of organization determination decisions where appropriate. We also agree that pre-service or concurrent reviews of inpatient services will generally satisfy the medical exigency standard and that MA plan determinations should be made on an expedited basis. Modifying Reopening Rules Related to Decisions on an Approved Hospital Inpatient Admission ACPA strongly supports prohibiting the reopening of approvals of inpatient care on the basis of “new and material evidence” which is merely information that became available throughout the course of the patient’s hospital stay. The inpatient decision is made based on the information available at the time of the decision, and per the Medicare Benefit Policy Manual, Chapter 1, post-admission information can only be used to “support a finding that an admission was medically necessary.” Because of CMS’s current and proposed interpretation of §422.566(c)(2), a reopening of an inpatient decision would not be appealable by the enrollee since it would be after a claim request for payment, thus making absolutely necessary the protections proposed by this section. Prompt Payment Clarification We appreciate CMS’s comment at 4208-P p. 99462 explaining “[w]hen a request for payment for furnished services is received without a previously approved coverage decision, the MA organization will apply coverage criteria and must either make payment or deny the request within the timeframes specified in the ‘‘prompt payment’’ provisions of §422.520.” While it may not have been CMS’s intent to address prompt payment rules under its proposal, this comment may warrant further clarification from CMS. MA organizations have widely maintained that the provisions of 42 C.F.R. § 422.520 with respect to prompt payment and interest are merely obligations between the organization and CMS, but do not create any direct responsibility of the organization or its plan(s) to remit interest to the provider to whom such payment is owed promptly. Confirmation from CMS that the prompt payment provisions of § 422.520 do in fact create a responsibility of MA organizations to pay covered services within the regulatory prompt payment time frame and, if it fails to do so, much include interest, is appreciated. ACPA appreciates CMS’s efforts to improve the function and efficiency of the Medicare Advantage program, and the opportunity to comment on this proposed rule. Thank you for your consideration to the changes outlined above and in the 2026 MA Plan proposed rule that will help hospitals continue to serve the Medicare Advantage beneficiary population. Sincerely,

Clarissa Barnes, MD |